Pauwels, Eric

1953 Antwerp (Belgium). Lives and works in Brussels.

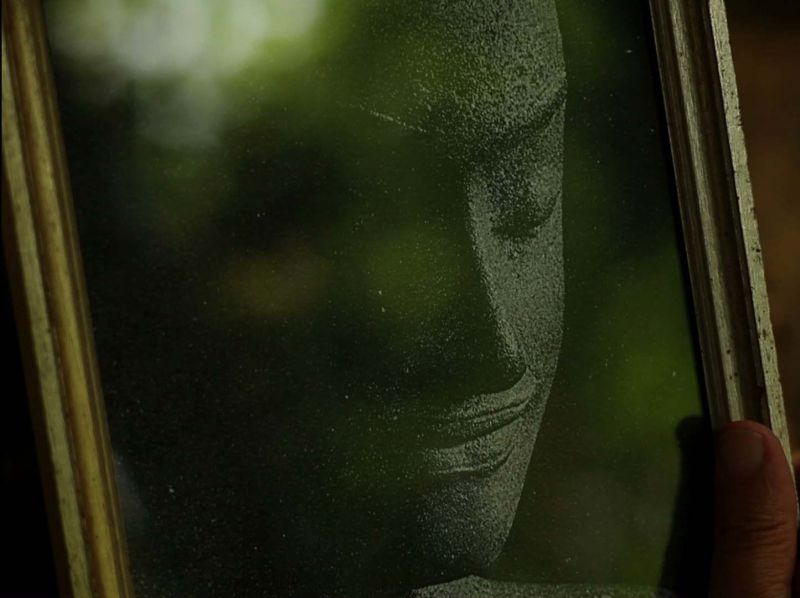

Filmmaker, writer and film lecturer Eric Pauwels started his career with what he calls ‘cinéma mémoire’, or ethnographic documentary. He obtained his PHD in cinematography in Paris with a documentary on the ‘possessed’ in Indonesia. Afterwards, eager to step out of his role of being a spectator, Pauwels begins to make dance videos and works of fiction. The latter are so-called ‘half films’: half documentary, half fiction. But which distance does one keep to one’s subjects? Pauwels’ answer is clear: eliminate the distance and become a subject amongst your subjects. For him, cinema and life should ideally coincide; fiction should penetrate documentary.

º 1953, lives in Brussels (Belgium).

The roots of the filmmaker, author and director Eric Pauwels can be traced back to what he refers to as ’cinéma mémoire’: the ethnographic documentary. That is where he ended up out of a fascination for the actor. After an education in theatre direction, Eric Pauwels got his doctor’s degree in cinematography from the Sorbonne (under tuition of ethnographer Jean Rouch). He is a film lecturer at the IHECS (in Mons) and the INSAS (in Brussels).

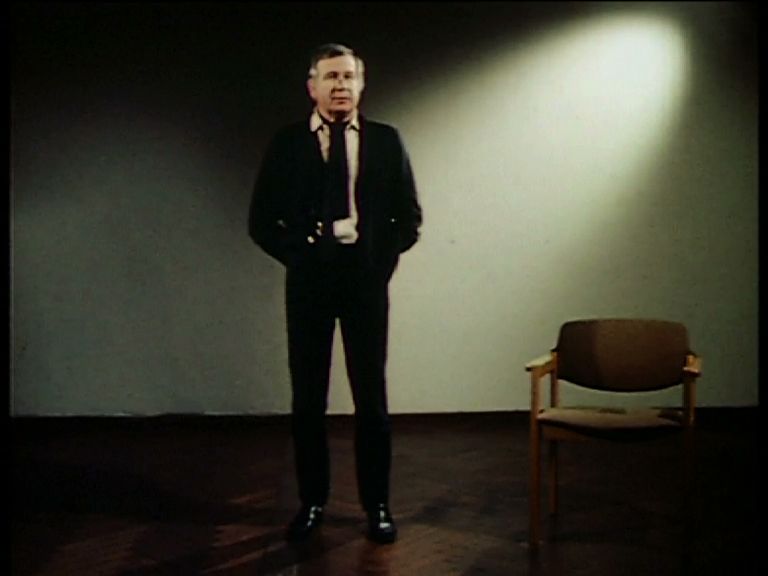

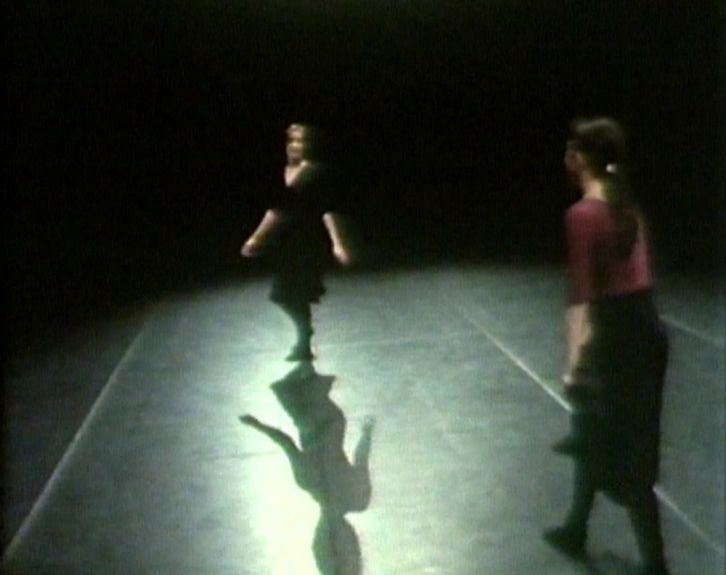

Pauwels wondered what inspires an actor and in search of an answer to this question he studied rituals of the possessed in Indonesia for two-and-a-half years: in his own words ’primitive’ theatre. This primitive theatre does not involve actors or dancers. Pauwels refers to them as ’actants’. The ’actant’ stands closer to the shaman: he is a dancer, ventriloquist, clown, tragedian and his own orchestra. In a tradition where people are familiar with rituals and ceremonies, the ’performance’ is not the grateful object of attention. There is also the audience: the spectators who observe the possessed. As time went by Pauwels gradually stepped out of this role of the spectator and the way of filming that went with it. In his dance-videos he creates a new relationship between himself and his subject. Body/dance, dance/cinema. These two dimensions are often found together in the history of film: the body as remembrance/memory, the image as scripture (writing with light). Verifying, pursuing, filming is always an act equated with a double goal. On the one hand it is an act of memory: a recording so that we might remember what happened. On the other hand it is an attempt at renewal in scripture itself. Filming dance often means dealing with this contradiction: showing the performance in its choreographic dimension, in its duration; but also rewriting the body of the dance in the movement of the camera, in the editing. Filming the body, its architecture, and its movement, its energy and beyond that the relationship this body develops with the spectator: this means being confronted once again with the basic questions of cinema. A question is put forward to the spectator (how to film, dance, live this dance?), and also to the demonstrator (how to pass on/ convert the choreography and the energy of the body?). Main topic is always the human being, his body, substance and skin. Pauwels’s cinema is characterised by a human attitude, eye to eye with the live and unique event that takes place in front of the camera. The eye, or rather the body, observing this event is sensitive, always looking for the right distance, the right frame. It enters a dialogue. E.g. in Violin Phase (1985) he twirls the camera around the body of Anne Teresa de Keersmaeker. What we see is not the geometrical and minimalist choreographic structure, but a possessed woman, bathing in sweat, exploring the boundaries of physical exhaustion. A solo in two movements: the dance and the camera. Four uninterrupted takes. Pauwels is constantly looking for the essence, the soul of cinema. In its explicit presence the camera is also driven to its extreme, perspiration, hardship. Pauwels is not concerned with beautiful shots, but with the investigation. With Improvisations (1986) he realised a plan-sequence of an improvisation by Pierre Droulers to the music of Thierry de Mey. The camera is situated against the unknown, explores space and the body that is moving in that environment. It turned into a battle, at times a dialogue, at times a rebuke. Trois danses hongroises de Brahms (1990) has the same outset: Pauwels participates in every dance. The difference is that for this production everything was meticulously prepared. Nothing was left to coincidence. The filmmaker and the dancers pass by each other; the camera makes sudden movements. This camera manipulation and the play with fore- and backgrounds created a tension between arrangement and spontaneity, between arrested and free movement, between frozen and unobstructed energy.

One of the most important questions during the making of a film is determining the distance to the subject. Pauwels’s answer to that question consists in the elimination of that distance: he becomes a subject amongst the subjects. Cinema and life coincide. Next to dance videos Pauwels went on making his documentaries. Or rather, his ’half-films’. Because the border line between fact and fiction is often bent. An example of this is Un Film (1986). Three people (3 actors: Josse De Pauw, Patrick Legrand, Michèle-An De Mey) spend the last days of the year travelling through the landscape of French Flanders and the North Sea coast. Legrand functions as a cameraman: he films the trip with a rattling super 8-camera. The couple, the farmers, himself. During the account the roles are reversed: the cameraman is being filmed. The recording gives way to fiction. The objective report turns into a subjective story. A similar thing happens in Lettre à Jean Rouch (1993) or in Lettre d’un cinéaste à sa fille (1999). The way it goes with memories interpretations, wishes, facts and own associations melt into one another, until no objective possibility is left to report on a journey, until it becomes clear what film language means to Pauwels.